1Learning Outcomes¶

Get acquainted a brief history of computers

Understand why writing programs in C allow us to exploit underlying features of the architecture (intentionally or unintentionally)

🎥 Lecture Video

2From ENIAC to EDSAC¶

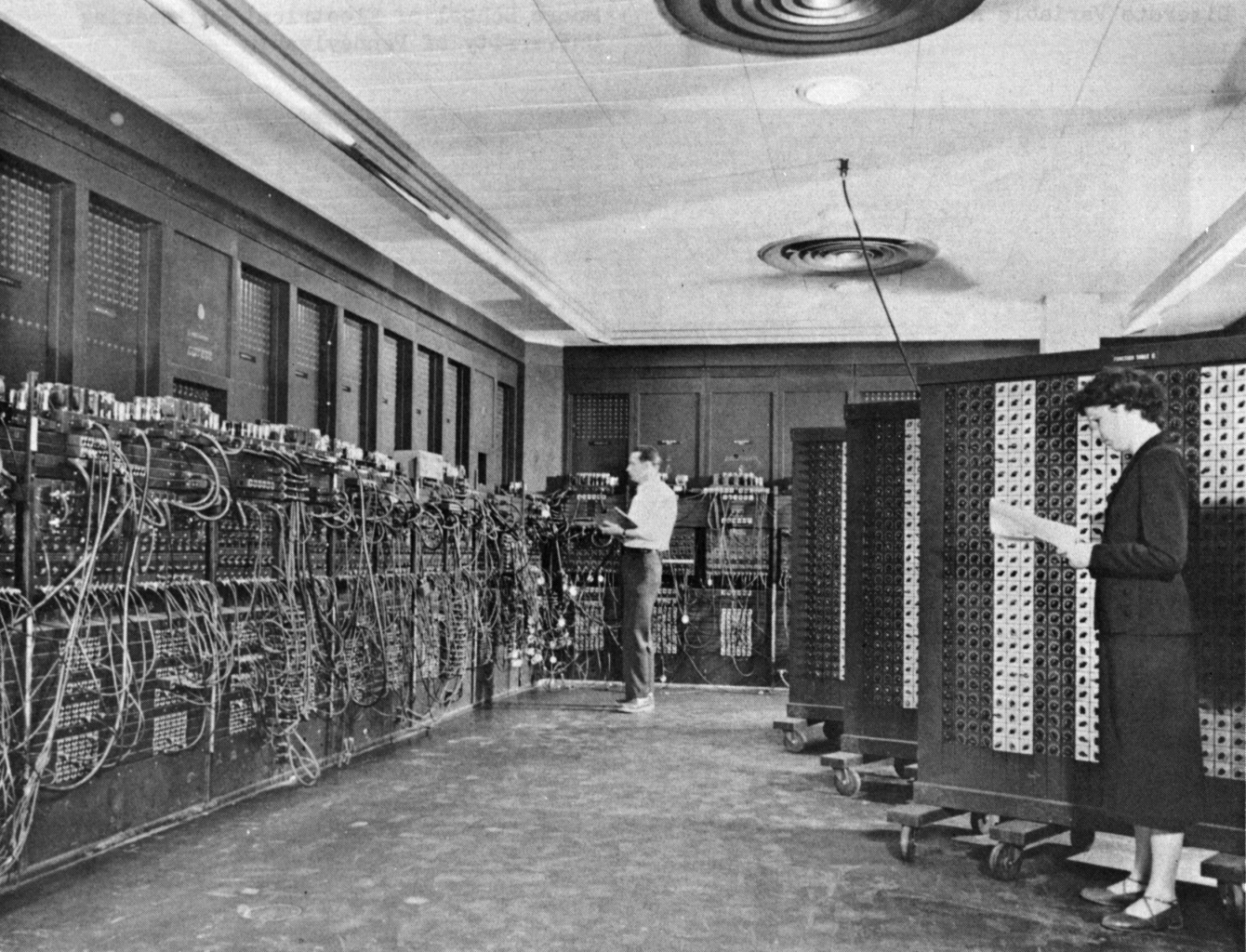

Let’s understand a little bit about the basics of computer organization. One of the earliest computers was the ENIAC at UPenn in 1945-46.

Figure 1:The ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was the first programmable, electronic, general-purpose digital computer, completed in 1945. (Wikipedia)

The ENIAC the first electronic general-purpose computer. Following World War II, it was often used to compute trajectories of ballistics. It multiplied in 2.8 milliseconds! The problem is, it took two or three days to program.

Note the patch cords in Figure 1; after reading the schematic, a human would write the patch cords. Not to mention—vacuum tubes were breaking all the time.

Let’s take a moment to also recognize the folks you see in the picture. Many of the first programmers were computers:

The women who worked for NASA ... were calculating equations to help improve the flight characteristics of airplanes. Engineers would work on the design and map out the equations. The equations would then be delivered to a computer, a woman, for calculating.

Early programmers were often women who were part of the UPenn group, and they don’t get enough press for being among the early programmers of the day. Watch the movie Hidden Figures (2016) to learn about these early female programmers and mathematicians.

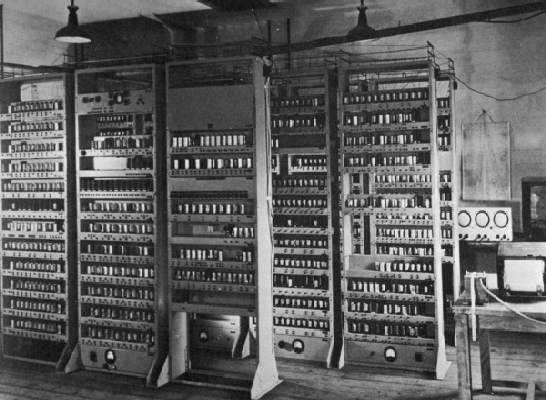

Next, the EDSAC at Cambridge (1949) was the first general stored-purpose computer.

Figure 2:The EDSAC (Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator) was one of the first general stored-program computers, completed in 1949. Wikipedia

Notice that Figure 2 no longer has patch cords. The EDSAC was designed around an astounding concept: the stored program, meaning that data doesn’t just have to represent numbers; it can represent the program itself. It meant that bits can be bits, and bits can be a program, too. Nowadays, we take this concept for granted; we download an app on our phone and we don’t even think about it.

Side note: At the time, the notion of the 8-bit byte was less standard. The EDSAC used 35-bit binary two’s complement words to represent a range of information, from integers to program instructions.

3Great Idea #1¶

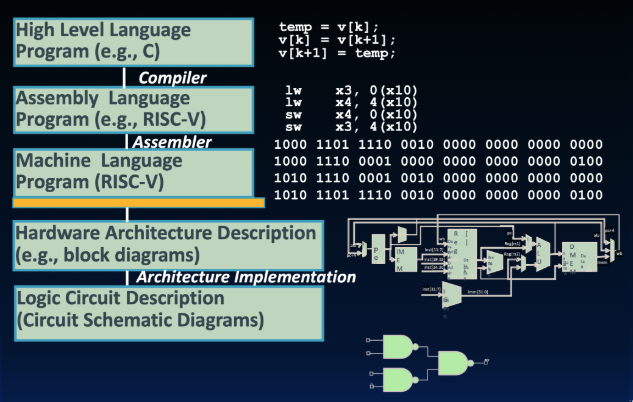

Abstraction. Anything can be a string of bits: data, numbers, instructions, etc.

Throughout this course, we will see how all of the layers in Figure 3 are tied together by this idea.

Figure 3:Great Idea #1: Abstraction. Anything can be a number: data, instructions, etc.

4High-level programming languages¶

In Figure 3, we refer to C as a high-level language. This will seem ridiculous to you: After all, Python is high-level, and C is low-level. A high-level programming language is a language that often deals with variables, loops, etc., instead of the specifics of processor architecture.

High-level language code compiles down to assembly code, which then is then assembled into machine code (i.e., bits). We will revisit these two low-level program representations very soon.

Back in the day, C was revolutionary. It facilitated the first operating system (Unix) not written in assembly. Unix is a portable OS, meaning you can write the code for the OS and then move it to a different architecture. That was a big deal! If you write in assembly, you have to customize it for that specific machine. But if you can compile it down from a level above—that’s abstraction, the most important idea in this class.

5Why C?¶

C is not a “very high-level” language, nor a “big” one, and is not specialized to any particular area of application. But its absence of restrictions and its generality make it more convenient and effective for many tasks than supposedly more powerful languages.

1. Learn computer science, not programming languages. At Berkeley, we take pride in having three different languages in our lower division EECS courses: Python, Java, and C. The goal is never just to teach you a language; it’s to teach you computer science. We want you to be fluent so you can decide which language to choose for a particular problem.

2. Exploit underlying features of the architecture. We learn C in this class because we can then write programs that involve memory management, parallelism, and more. However, note that C is low enough to the silicon that you can be poking at bits and have more control. It also makes it hard to program!

We’re going to show you how much trouble you can get into with pointers and memory leakages. C is not strongly typed, so the compiler can’t check everything. It’s almost like a car where you’ve stripped away all the plastic and all you have is wires... and you’re jump-starting it by rewiring those wires. Fun times. More later.

3. After over 40 years, one of the most popular programming languages is C (and its derivatives, C++, Objective C, C#). We will soon see that Java adapted a lot from C—because most programmers were already familiar with C syntax.

6C: Disclaimers¶

C is much more “low level” than other languages you’ve seen. It is inherently unsafe (more later), has terrible keyword conventions, bizarre variable scoping, ..., the list goes on.

All things considered, C is a reasonable choice for teaching introductory computer architecture. When you write programs in the real-world, however, you have better options, depending on what sort of program you’re going for.

If performance matters:

Rust is like a “C but safe” language—if you want the power of C but with more safety. By the time your C program is (theoretically) correct w/all necessary checks, it should be no faster than Rust.

Go: “Concurrency”: Practical concurrent programming takes advantage of modern multi-core microprocessors.

If scientific computation matters:

Python has good libraries for accessing GPU-specific resources. The Python interpreter is written in C. Python can use Cython to call low-level C code to do work. Pytorch, a popular Python library for machine learning, uses C++

Spark can manage many other machines in parallel.

6.1The C Language Is Constantly Evolving¶

The C programming language standard has had several significant revisions since its inception in 1972. Just like Python2 vs Python 3 – same language, but slightly different syntax/features.

A history, from StackOverflow:

Pre-1989: K&R C (note K&R 1st ed 1978, 2nd ed 1988)

1989/1990: ANSI C

1999: C99

2011: C11

2017: C17

2024: C23

We will teach the C17 standard in this course, which is the version of C assumed by gcc on our course servers. What’s gcc? You’re about to find out!

6.2Try it yourself!¶

Final disclaimer: you’re not going to learn to code C just by watching videos or reading a book. You have to try it yourself. Go grab an editor and start firing it up!

We will try our best to cover the key aspects of the C language in these course notes. But you should still have a C reference handy. The K&R book (Kernighan & Ritchie, 2nd edition, 1988 the version with the ANSI red logo) is a must-have for every C programmer.