1Learning Outcomes¶

Contrast the heap’s dynamic memory with stack memory.

freeevery block allocated withmalloc,realloc, orcallocPractice reading Linux

manpages to determine specific behavior of Cstdlibfunctions.

🎥 Lecture Video

Until 9:36

2Dynamic memory allocation on the heap¶

Dynamic storage on the heap comes in handy when we must maintain persistent, resizable memory across function calls, such as when we write programs to build data structures through different function calls.

The closest analogy in Java is use of the Java keyword new, which dynamically allocates memory for an object. However, Java has a background garbage collector which frees dynamically allocated objects when they are unused. In C, we need to manually free space on the heap; we even need to manually resize space if we run out. These key differences lead to the biggest source of C memory leaks and bugs in more complex programs beyond the scope of this course.

Memory on the heap is managed with the help of standard C library functions in stdlib.h:

malloc: memory allocation, i.e., allocate a memory block on the heapfree: free memory on the heaprealloc: reallocate previously allocated memory blocks to a larger or smaller memory block on the heap.

Let’s first describe heap operation at a high-level, then dive into the function signatures for each of these functions. This will inform potential pitfalls and details that we did not need to consider with stack memory.

3Heap operation¶

Let’s first describe the heap in contrast to the stack. Dynamic memory (that is, storage in the heap) can be allocated (malloc-ed), resized (realloc-ed), and deallocated (free-d) during program runtime. We therefore do not necessarily need to know all sizes of memory blocks on the heap at compile-time; contrast this with the stack, where each local variable size must be determined first in order to determine the size of each stack frame.

The stack is a relatively small pool of memory, and memory blocks are allocated as stack frames, which are adjacent to one another. By contrast, the heap is typically huge–much larger than the stack—and memory blocks are not necessarily allocated in contiguous order.

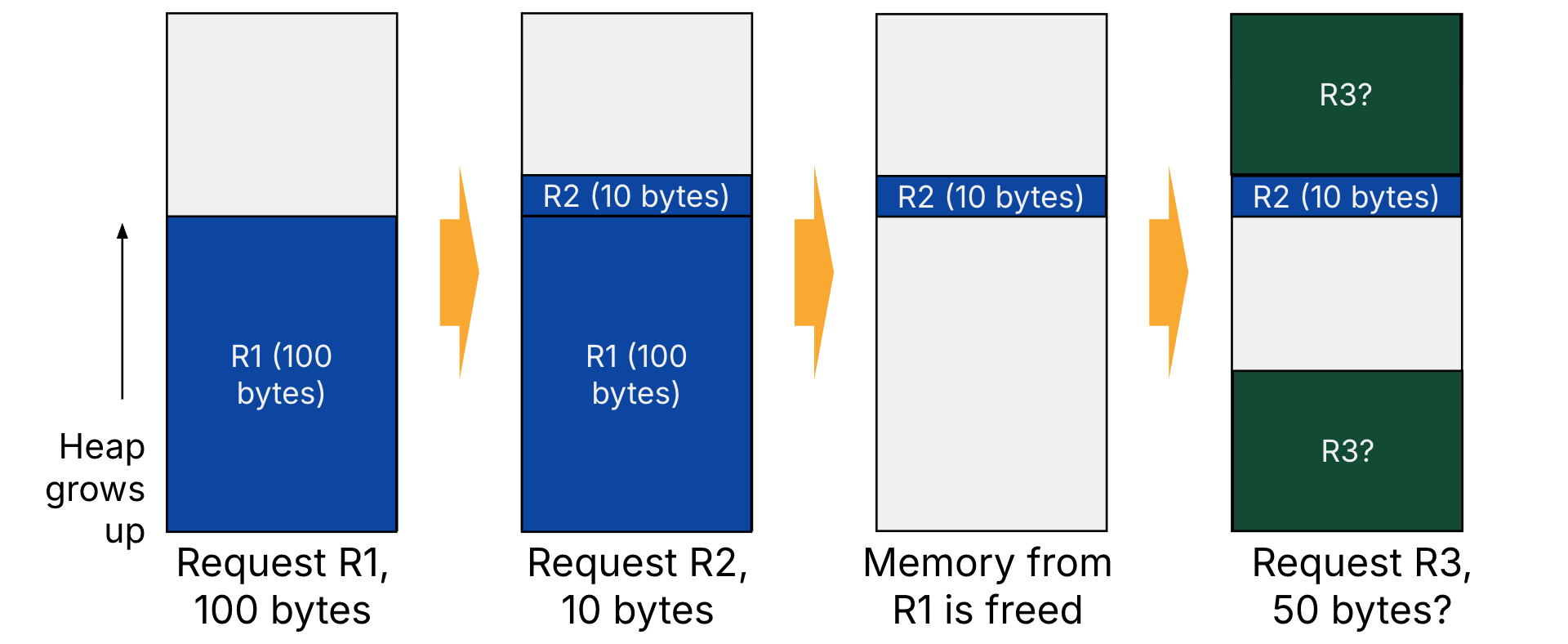

The precise location of heap memory blocks is delegated to a built-in heap allocator implemented in the C standard library (read more in this chapter’s optional section). Figure 1 visualizes how a heap allocator might handle four memory requests.

Request R1:

malloc100 bytes of space. The heap allocator finds a block low in the heap.Request R2:

malloc10 bytes of space. The heap allocator finds a block close to R1.freethe 100 bytes of space from request R1. The heap allocator marks the original block deallocated and available for future requests.Request R3:

malloc50 bytes of space. The heap allocator may choose to allocate part of the block originally allocated for R1, or it may choose to put it somewhere entirely new. Both of these risk fragmenting the heap, preventing contiguous blocks for future requests.

Figure 1:main passes its own local variable buf into a function call load_buf.

We do not expect you to know how a heap allocator decides where to allocate memory (see this chapter’s optional section if you are curious). Instead, know that we must be careful to assume anything about the memory locations we get back from heap functions. We can only trust that a single request will return a contiguous block of memory; however, back-to-back heap memory requests can result in blocks that are quite far apart.

4C stdlib functions for heap management¶

4.1void *malloc(size_t n)¶

malloc is a function that takes in the number of bytes you want and returns a pointer to uninitialized space. In other words, the n bytes starting at that pointer initially contains garbage.

Parameter

size_t n: An unsigned integer type big enough to “count” memory bytes.Return:

void *pointer, i.e., a pointer to generic space (read more in a future section). A return valueNULLindicates there is no more memory available on the heap.

Assuming size of objects can lead to misleading, unportable code, so we use sizeof in the below examples[1].

1 2 3typedef struct { ... } treenode_t; treenode_t *tp = malloc(sizeof(treenode_t)); if (!tp) { ... }

uint32_ts:uint32_t *ptr = malloc(20*sizeof(uint32_t));Check for NULL: We always want to check if malloc succeeds, so that we can safely exit instead of crashing. Contrast this failure mode with that of main, where returning a zero is success. Here, we know there is precisely one value that will never be a valid memory address: NULL, which upon access crashes your program.

Typecast malloc’s return value. Generally, we will typecast the returned generic pointer to a typed pointer. This means we will interpret the address returned by malloc as the location of a particular variable type. For example, if we are allocating heap space for a uint32_t array, typecasting to a uint32_t * pointer will facilitate pointer arithmetic, array access, and integer operations.

Show Answer

Line 1:

typedef structdoes not allocate memory. It simply definestreenode_t.Line 2, RHS (right-hand side):

malloc(sizeof(treenode_t))allocatessizeof(treenode_t)bytes of memory on the heap.Line 2, LHS (left-hand side):

treenode_t *tpis a local variable. This declaration allocates at leastsizeof(tp *)(i.e., the size of a pointer) onto the stack frame. Based on just the C code, we can’t specify exactly how much data is allocated for the full stack frame, but it must be at leastsizeof(tp *)unless the C compiler decides to optimize with hardware registers (more later).

4.2void free(void *ptr)¶

free is a function that takes in a pointer on the heap to free.

Parameter

void * ptr: A pointer containing an address originally returned bymalloc/realloc.Returns: No return value.

Because the C heap does not do automatic garbage collection, as C programmers we must always free memory that we allocate on the heap. A good analogy draws from the film Godfather (1972)[2]:

... It’s almost like going to the Godfather and asking for a favor.

You: [clasps hands] Godfather...I would like some some memory from you...

Godfather: [strokes pet cat] Some day–and that day may never come–I may call on you to do a favor for me. But until that day, I will give you this with

mallocunder the contract that you must free it when you are done...

uint32_t *ptr = malloc(20*sizeof(uint32_t));

...

free(ptr); // implicit typecast to (void *)If you do not free memory, you risk memory leaks–meaning that memory is allocated but never accessed on the heap, and you will eventually run out of memory. For long-running programs like servers, memory leak errors may lead to hard-to-debug crashes way, way into runtime.

If you do not free memory properly, your program will crash or behave very strangely later on, causing bugs that are VERY hard to figure out. Here’s the corresponding segment of the Linux manual page (type in the command man free):

The free() function shall cause the space pointed to by ptr to be

deallocated; that is, made available for further allocation. If

ptr is a null pointer, no action shall occur. Otherwise, if the

argument does not match a pointer earlier returned by a function

in POSIX.1‐2008 that allocates memory as if by malloc(), or if the

space has been deallocated by a call to free() or realloc(), the

behavior is undefined.In other words, when you free memory: pass in the original address returned from malloc, and do not “double free”. These arguments will produce undefined behavior. For example, passing in ptr+1 would still technically point to somewhere in the original memory block, Above, the start of the malloc-ed heap block is the address stored in ptr. While passing in ptr+1 would still technically point to somewhere within this memory block, depending on how free is implemented, free(ptr+1) may crash the program...or worse...

Why does the heap not check for these mistakes in runtime? In C, memory allocation is simply so performance-critical that there just isn’t time to do this. The usual result is that you somehow corrupt the memory allocator’s internal structure, and you won’t find out until much later on in a totally unrelated part of your code. It’s like not brushing your teeth regularly; you’ll pay for it years later, and via symptoms not related to your teeth...

4.3void *realloc(void *ptr, size_t size)¶

realloc is a function that resizes a previously allocated block at ptr to a new size. In doing so, it may need to copy all data to a new location.

Parameter

void *ptr: A pointer containing an address originally returned bymalloc/realloc, OR the valueNULL.Parameter

size_t size: An unsigned integer type big enough to “count” memory bytes."Return:

void *pointer, i.e., a pointer to generic space. A return valueNULLindicates there is no more memory available on the heap.

From the Linux man page:

If ptr is a null pointer, realloc() shall be equivalent to

malloc() for the specified size.

If ptr does not match a pointer returned earlier by calloc(),

malloc(), or realloc() or if the space has previously been

deallocated by a call to free() or realloc(), the behavior is

undefined.

The order and contiguity of storage allocated by successive calls

to realloc() is unspecified. The pointer returned if the

allocation succeeds shall be suitably aligned so that it may be

assigned to a pointer to any type of object and then used to

access such an object in the space allocated (until the space is

explicitly freed or reallocated). Each such allocation shall yield

a pointer to an object disjoint from any other object. The pointer

returned shall point to the start (lowest byte address) of the

allocated space. If the space cannot be allocated, a null pointer

shall be returned.

...

RETURN VALUE

Upon successful completion, realloc() shall return a pointer to

the (possibly moved) allocated space. If size is 0, either:

* A null pointer shall be returned and, if ptr is not a null

pointer, errno shall be set to an implementation-defined

value.

* A pointer to the allocated space shall be returned, and the

memory object pointed to by ptr shall be freed. The

application shall ensure that the pointer is not used to

access an object.The below code discusses each of these points:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14uint32_t *ip; /* 1 */ ip = realloc(NULL, 10*sizeof(uint32_t)); if(!ip) { ... } // check for NULL ... /* 2 */ ip = realloc(ip, 20*sizeof(uint32_t)); if(!ip) { ... } // check for NULL ... /* 3 */ realloc(ip, 0);

4.4void *calloc(size_t nelem, size_t elsize);¶

Many C programmers prefer to use calloc for allocating memory because, unlike malloc, it initializes all bits in the allocated block to zero. From the man page:

The calloc() function shall allocate unused space for an array of

nelem elements each of whose size in bytes is elsize. The space

shall be initialized to all bits 0.Like with malloc and realloc, any pointer returned by calloc should be always checked for NULL first.

The implicit typecast shown in this section casts the return value of

mallocfrom type(void *)to, say,(treenode_t *)and assumes it works. In modern C, the implicit typecast is fine. In pre-ANSI C, however, implicit pointer typecasting produces a warning, so explicit typecast syntax liketreenode_t *tp = (treenode_t *) malloc(sizeof(treenode_t)is preferred. Finally, C++ is a different language entirely, and such implicit pointer typecasts will produce errors. These differences are important to keep in mind when you are porting C code between systems. Read more on StackOverflow.Watch the lecture video for a good Godfather (1972)impression. Timestamp 3:24