1Learning Outcomes¶

Understand how the stack pointer automatically allocates and deallocates stack frames.

Understand when it is safe to pass pointers into the stack between functions.

🎥 Lecture Video

8:37 onwards

2How the Stack Works¶

The Stack is a contiguous block of memory that starts from high addresses and grows downwards. Every time a function is called, a new stack frame is allocated on the stack as a contiguous block of memory. This stack frame includes space for the following:

local variables declared within the function

a return address, i.e., the instruction address in the text segment that should be next accessed after this function finishes execution [1]

function arguments [1]

Allocation and deallocation is incredibly fast on the stack thanks to the stack pointer. The stack pointer is an internally tracked value[2] that tells us the address of the “top of the stack”, i.e., the start of the current frame, and thereby determins allocation and deallocation on the stack.

The Stack segment manages stack frames like a stack data structure: Last In, First Out (LIFO). “Grow” the stack by moving the stack pointer down to a lower address, thereby pushing on a “new stack frame” (i.e., a new block of memory). “Shrink” the stack by moving the stack pointer back up to a higher address, thereby popping off the current stack frame.

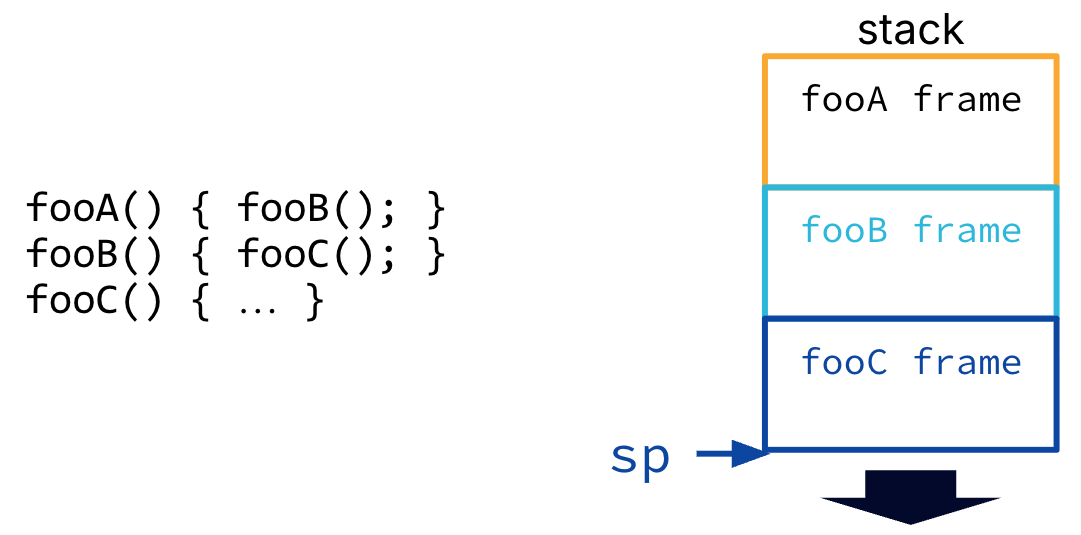

In Figure 1, notice the stack’s downward growth means that fooB()’s local variables have lower byte addresses than the variables in its caller fooA(), and so on.

Figure 1:The stack grows downward. The stack pointer (sp) points to the top of the stack, i.e., the address of the current stack frame.

The slidedeck in Figure 2 animates allocation and deallocation on the stack via the stack pointer.

Figure 2:An extended animation of stack memory management.

Explanation of Figure 2

In Figure 2:

main()is called as soon as the program loads. One stack frame formainis allocated by moving stack pointerspdown to the start of this new frame (recall: blocks of memory are referred to by their lowest address).a(0)is called bymain.spmoves down. Local variables foraare initialized in stack memory starting fromspand going upwards.spcreates enough space to store local variables, whose sizes are known at compile-time. So there is no risk that initializing these variables will spill intomain’s frame.b(1)is called bya. Stack frame forbis allocated right below stack frame ofb. Stack pointerspmoves down to the start of this new frame.c(2)is called byb, etc.d(3)is called byc, etc.When

dfinishes executing, “return” control to the caller functioncby (1) setting the next instruction to execute to the return address[1], and (2) popping off the stack frame, i.e., updatingspto the end of stack frame ford, which is also the start of the stack frame forc.cis now the function to continue executing.When

cfinishes executing, return control tob, etc.When

bfinishes executing, return control toa, etc.When

afinishes executing, return control tomain, etc.When

mainfinishes executing,spnow points to the highest address of the stack, and there are no stack frames left on the stack. End the program.

Consider Figure 2. If you had a secret password like "Bosco" stored in a local variable in function d(), and function d() returns, that "Bosco" string is still in memory even though you aren’t supposed to access it. You can see this if you follow a pointer to a returned local variable; the first time you print it, it might still show the old value (like 3), but the next time you call a function like printf, that new function call creates its own stack frame and clobbers the old data.

3Passing pointers into the stack¶

At this point in your programming livelihoods, you have likely found it useful to pass data from one function to another function. We now also know that pointers into the stack may point to stale data, if the corresponding local variable’s function has already finished executing! In these cases, C will not throw an error, but your program may have undefined behavior.

Consider this warning we saw in an earlier section.

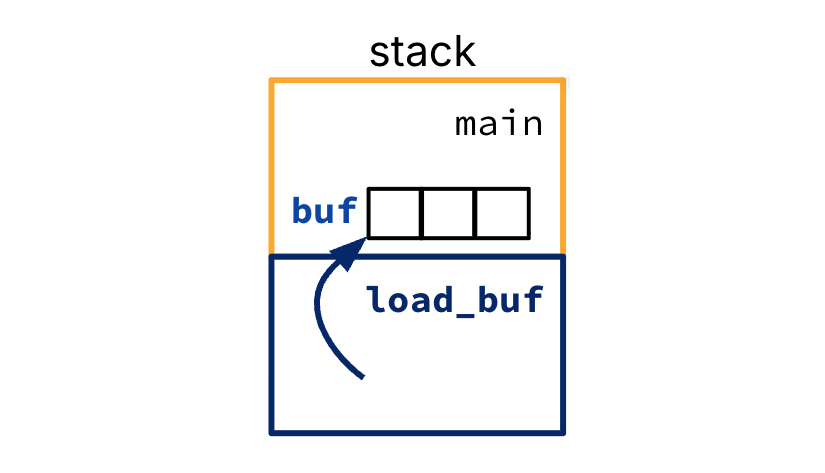

The code snippet below corresponds to the stack memory layout in Figure 3. This code structure is common when load_buf loads data from, say, a file into a particular memory buffer. main first allocates len bytes of space[3] for the buffer in its local variable buf, then calls load_buf, then processes the data in buf.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10void load_buf(char *ptr, size_t len) { ... } int main() { ... char buf[...]; load_buf(buf, BUFLEN); ... }

Figure 3:main passes its own local variable buf into a function call load_buf.

All stack frames currently on the stack correspond to function calls that have not finished executing. In Figure 3, the main stack frame exists until load_buf (which main calls) returns, and then some. load_buf can “trust” that the len bytes of stack memory starting at ptr will persist throughout execution of the function and can confidently write to this area of the stack.

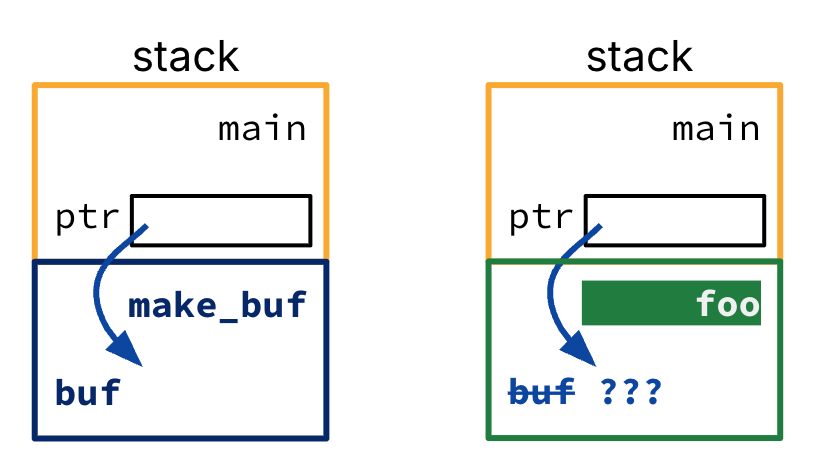

The code snippet below corresponds to the perilous stack memory layout in Figure 4. Here, main still wants to load and process data from a file, but it does so by first making the buffer in a make_buf function call, then calls foo to process the data.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10char *make_buf(size_t len) { char buf[len]; return buf; } void foo(char *ptr2, size_t len) { ... } int main(){ char *ptr = make_buf(BUFLEN); foo(ptr, BUFLEN); ... }

Figure 4:Left: Stack layout when make_buf returns. Right: Stack layout when foo is executing.

main has a local variable pointer ptr. In Line 7, ptr is updated to an address within make_buf, which has already returned. We call this a dangling reference, because ptr points to deallocated memory.

The address stored in ptr is a location of the stack below the main stack frame. When foo gets called in Line 8, the foo stack frame will reference the memory below the main stack frame, right where ptr supposedly points to! There is no guarantee that the len bytes at the address ptr will not be used for other data.

While we could hack together something that works for this toy example, consider that there may be many additional functions called between main and foo. If foo itself calls a system function, say, printf, then there is even less chance that ptr is not corrupted by other function calls.

Above all, remember that memory lower in the stack is overwritten when other functions are called.

(same exact footnote as in an earlier section) Because parameters and return addresses are critical to function call and return, they are stored directly in the CPU where possible–on special hardware called registers (which we talk about later). Because there are only a limited number of such registers, additional parameters and return addresses are stored in memory on the stack until they are needed.

The stack pointer itself must live somewhere. Instead of living in memory, it lives on the CPU in a special hardware register, so that it can be read and updated quickly. This is a detail we handwave for now and discuss in detail later.

unsigned integer type big enough to “count” memory bytes.