1Learning Outcomes¶

Distinguish between a memory address and a value in memory.

Get familiar with the paradigm of byte-addressable memory, i.e., that each byte in memory has an address, and each address refers to a byte location in memory.

Understand that pointers are variables that store addresses.

🎥 Lecture Video

1:39 - 4:22

2Memory Is Like a Byte-Addressable Array¶

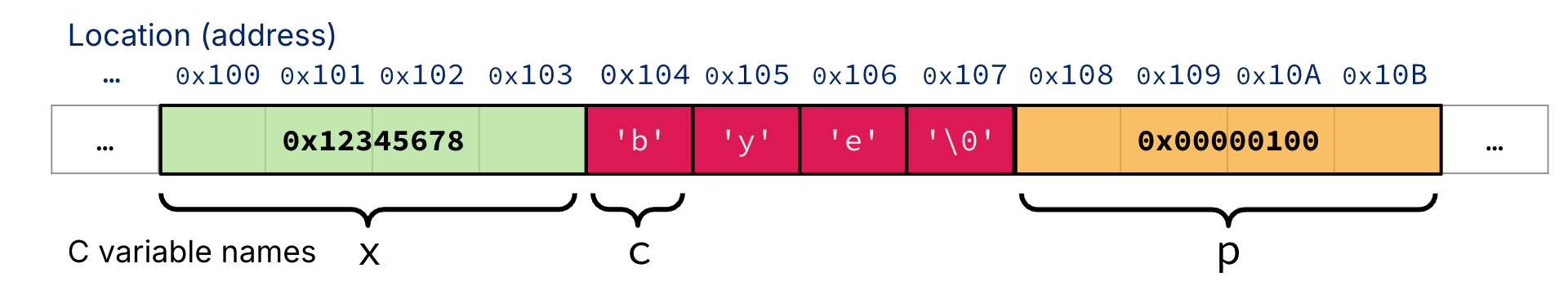

For now, imagine all your memory as one really big, infinitely large array starting at zero, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:One view of memory as a single huge array, where each byte has an address.

Think of this array as a very, very, very long street with lots of houses. Each cell is a house; the cell has someone living inside (e.g., a byte of data), and the cell also has a house address (e.g., a memory address). We worry about the range of addresses later; assume the street is infinitely long, but it starts from 0x0000000 (the all-zero address).

In this analogy, each cell of the array is one byte wide. Each byte, then, has an address associated with it, and the byte itself is has a value. For example, the byte at address 0x00000104 (i.e., “@” 0x104) is the 8-bit pattern for the ASCII character 'b', or 0b01100010.

Variable names can often refer to memory locations–specifically, blocks of memory. In Figure 1, the variable x is (say) an unsigned 32-bit integer. The variable x has value 0x12345678. Its address, by convention, is the address of the first byte of the memory block, also known as the lowest address of the block. In the diagram, the address of x is 0x00000100.[^endiannness]

In this chapter, we will cover three very closely-related concepts that get us closer to understanding how memory works under the hood: pointers, arrays, and C strings. Each of these concepts come with their own benefits and pitfalls. Let’s dive in!

3Pointers store addresses¶

You may have heard through the grapevine about pointers. You may be scared of pointers (or of the grapevine)! The key to understand pointers is to really internalize its definition:

Pointer: A variable that contains the address of another variable.

In other words, it “points” to a memory location. This “pointing” analogy is somewhat confusing at first glance, so let’s demystify.

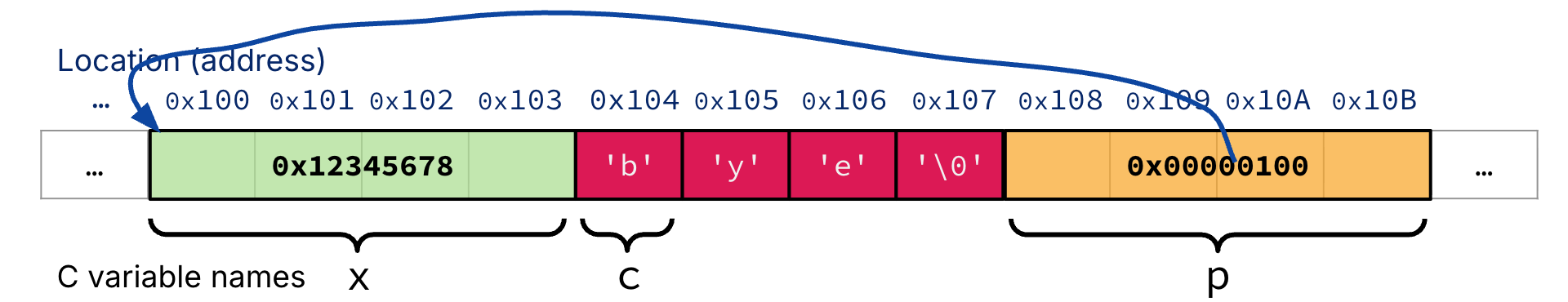

In Figure 2, the pointer p “points to” x. But everything in C is bits under the hood, what this actually means is that p is a variable that stores the address of x, or 0x00000100. While x is (for example) an unsigned integer that occupies 32 bits, the value of p is the address of the lowest byte of x.

Figure 2:The pointer p “points” to the location of x in memory. See the blue arrow.

Because pointers themselves are also variables, they can also have addresses. In Figure 2, p is stored at address 0x00000108.

Another phrasing you will hear is that you can “follow” pointers, meaning, we access the value that a pointer points to (a process we will formally call dereferencing). In this case, if we “follow” pointer p, we should get the value of x, which is 0x12345678.

To do so, C requires that all pointers are typed. If we knew that p was a pointer to a 32-bit unsigned integer, then we know that following the pointer p should get the 4 bytes starting at 0x00000100, not just the byte at 0x00000100 itself. We discuss this syntax in the next chapter.