1Learning Outcomes¶

Know C pointer syntax, including struct pointer syntax.

Know what the

NULLpointer is and why having aNULLpointer is usefulUnderstand that because C is pass-by-value, pointers facilitate updates to values in memory when performing function calls.

🎥 Lecture Video

1:39 - 4:22

🎥 Lecture Video

As we shall see in this section, pointers are incredibly powerful abstractions that help make C efficient. But with power comes great responsibility and lots of bugs. In this section, we will first get familiar with pointer syntax in C in order to understand when and where bugs pop up.

2Pointer Syntax¶

1 2 3 4 5int *p; int x = 3; p = &x; printf("p points to %d\n", *p); *p = 5;

2.1Lines 1-2: Pointer Declaration¶

To declare a pointer, use the syntax:

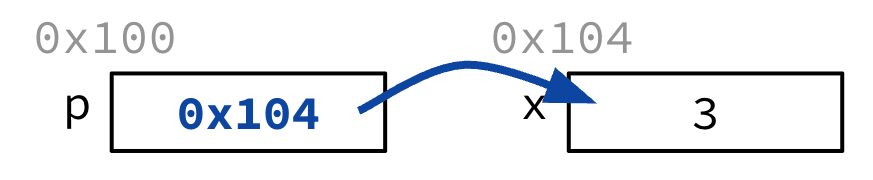

int *p;This line tells the compiler that the variable p is the address of an int. Like with all C variables, uninitialized variables contain garbage, as represented with question marks in Figure 1.

Figure 1:Declare a pointer variable.

2.2Line 3: The address operator, &¶

To get the address of any variable, use the syntax:

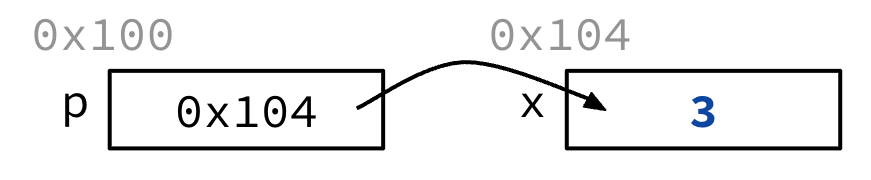

p = &x;The ampersand (&) is the address operator. Colloquially, we can describe Line 3 as “set p to point to x” or “set p equal to the address of x.”

In Figure 3, two visual cues show this assignment. First, there is a blue arrow going from the box for the variable p and pointing at the box for the variable x. Second, because diagram arrows don’t particularly translate well into bits, the value of p has been updated to the address of x, or 0x104.

Figure 2:Set p to point to x.

2.3Line 4: The dereference operator, *¶

Consider the next line:

printf("p points to %d\n", *p);We haven’t discussed format strings in much detail. Briefly, %d marks an integer placeholder in the format string. printf then interprets the first parameter as an integer to put into the placeholder, then prints the updated string to stdout.

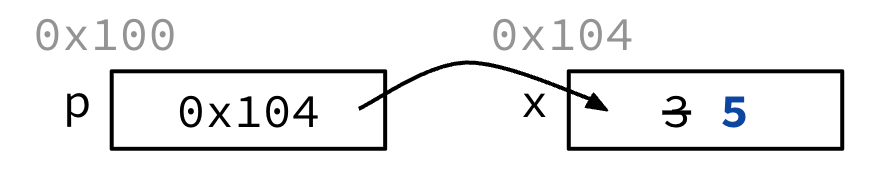

The star (*) is (also) the dereference operator. Colloquially, dereferencing means that we follow the pointer and get the value it points to. As shown in Figure 3, dereferencing p gets the integer value at 0x104, which is the integer 3.

Figure 3:Follow the pointer p, i.e., access the value that p points to.

The string printed to stdout is

p points to 32.4Line 5: Dereference and assign¶

The final line:

*p = 5;This syntax also uses the star * to dereference. Here, because it is on the left-hand-side of an assignment statement (=), C interprets Line 5 as setting the value that p points to. As shown in Figure 4, this updates the value at 0x104 to the integer 5.

Figure 4:Update the value that p points to.

Because this is a toy example, note that we could have also updated the value at 0x104 by assigning x to 3, e.g., x = 3;.

Up next, let’s see cases in which values must be updated with pointers.

3C is Pass-by-Value¶

The C programming language is pass-by-value, meaning that function parameters get a copy of the argument value.[1] While this property is useful to help evalute arguments before they are passed in as parameters, it restricts the values we can update.

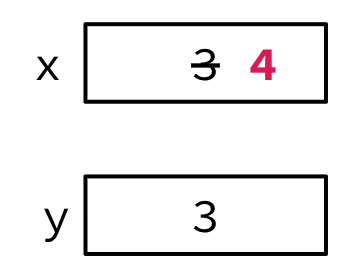

Consider the code. Updating the value of x within the add_one function does not update the value of y within main.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7void add_one(int x) { x = x + 1; } int main() { int y = 3; add_one(y); }

Explanation

Line 5: Declare a variable

yand set its value to3.Line 6: Pass a copy of

y’s value in and set it to the parameterxfor the functionadd_one.Line 2: Update

xtox + 1, i.e., setxto 4. Return from the function.Line 6, returned: the value at

yis still3.

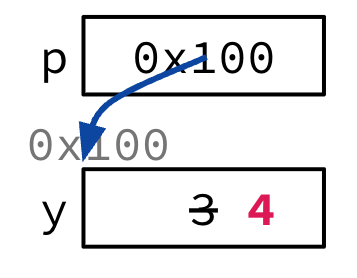

Figure 5:y is not updated.

To change a value from within a subroutine, we must use pointers. Consider the updated code below. main passes in the address of variable y, and add_one now has a pointer-typed parameter. The subroutine add_one now dereferences the pointer to modify the value at the original address of y.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7void add_one(int *p) { *p = *p + 1; } int main() { int y = 3; add_one(&y); }

Explanation

Line 5: Declare a variable

yand set its value to3.Line 6:

add_onenow expects a pointer argument. Use the address operator (&) to get the address ofyand pass that in. This is the value0x100, which gets set to the parameterp.Line 7:

Right-hand-side: Dereference

pto get3, then add one to get4.Left-hand-side: Assign the value pointed to by

pto4, i.e., set the 4 bytes starting at address0x100to the bit-representation for the integer4. Return from the function.

Line 6, returned: the value at

yis now updated4. This is becauseyis located at memory address0x100, and theadd_onesubroutine updated the value at this address, in memory.

Figure 6:y is updated from within the add_one function.

4Pointers: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly¶

At the time C was invented (early 1970s), compilers didn’t produce efficient code, so C was designed to give human programmer more flexibility. Given the pass-by-value paradigm, it was much easier to pass a pointer to a function instead of a large struct or array.

Nowadays, computers are hundreds of thousands of times faster than early computers, and compilers are much more efficient. That being said, pointers are still incredibly useful for understanding low-level system code, as well as implementation of “pass-by-reference” object paradigms in other languages.

While pointers can often allow cleaner, more compact code, they are often the single largest source of bugs in C. Be careful! They surface most often when managing dynamic memory and cause dangling references and memory leaks. Why? Because pointers give you the ability to access values in memory, even when you shouldn’t have access.

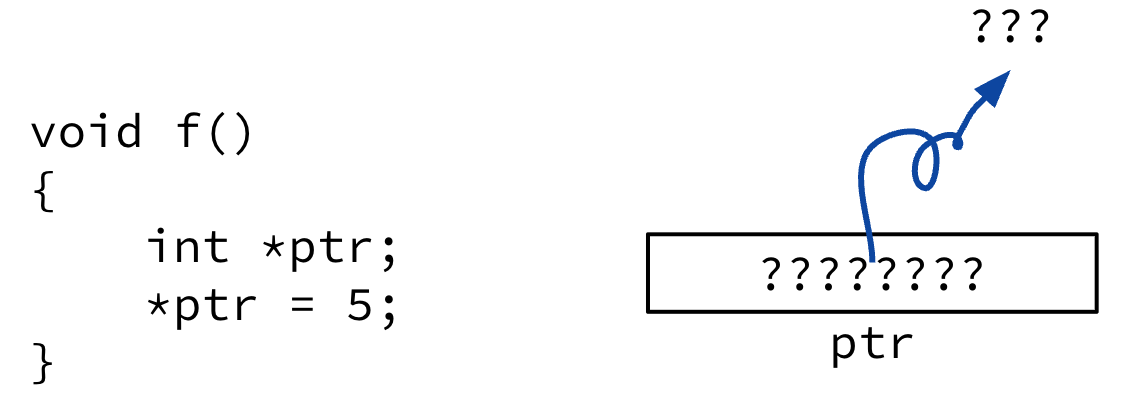

4.1Garbage Addresses¶

Here’s one example. Like all local variables in C, declaring a local pointer variable does not initialize it. It just allocates space to hold the pointer!

The example in Figure 7 shows code that will compile (albeit with a few warnings). In this case, ptr is allocated to space that should be interpreted as an int *, or as an address that has an int. Whatever bytes are there at the time of declaration are then interpreted as the address to store the value 5 in. Your program then exhibits undefined behavior. Wacko!

Figure 7:The bytes stored at ptr are interpreted as an address of an int. This code could potentially update 5 in a random part of memory.

5Using Pointers Effectively¶

At this “point,” we hope we haven’t scared you. You should still look forward to playing with pointers, despite their rough edges! Let’s discuss using pointers effectively.

5.1Pointers to Different Data Types¶

Pointers are used to point to a variable of a particular data type:

int *xptr;

char *str;

struct llist *foo_ptr;Explanation

int *xptrdeclares a variable calledxptrthat points to anint.char *strdeclares a variable calledstrthat points to achar.struct llist *foo_ptrdeclares a variable calledfoo_ptrthat points to astruct llist.

Declaring the type of a pointer determines how the dereferencing operator (*) works, i.e., how many bytes to read/write when we “follow” pointers.

Normally a pointer can only point to one type. In a future chapter we discuss the void * pointer, a generic pointer that can point to anything. In this course we will use the generic pointer sparingly to help avoid program bugs...and security issues...and other things... That being said, we will encounter generic pointers when working with memory management functions in the C standard library (stdlib).

We can also have pointers to functions, which we discuss in a future chapter. For now, if you are curious about the syntax:

int (*fn) (void *, void *) = &foo;

(*fn)(x, y);In the first line, fn is a function that accepts two void * pointers and returns an int. With this declaration, we set it to pointing to the function foo. The second line then calls the function with arguments x and y.

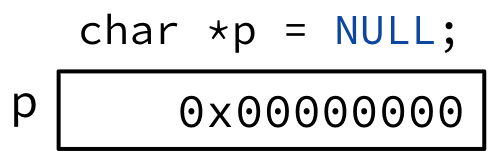

5.2NULL pointers¶

Regardless of pointer type, the pointer to the all-zero address is special. This is the NULL pointer, like Python’s None or Java’s null.

Figure 8:The compiler resolves NULL to an address of all zeros, i.e., where all bits are 0.

The address 0x0...0 is reserved, meaning that it is not permitted to read or write to that address; doing so causes a runtime error. While you may think that read/writing to a “null pointer” is bad news–because it causes your program to crash–this is actually incredibly useful as a “sentinel value.” What we mean is that setting a pointer to NULL tells us that it doesn’t point to a valid value in memory.

Recall that the boolean value false is all zeros. This means that it is very easy to check if a pointer is NULL or not! In the code below, !p will only resolve to true iff p is NULL.

if(!p) { /* p is a null pointer */ }

if(q) { /* q is not a null pointer */ }5.3Struct pointer syntax¶

We often like to use struct pointers because structs themselves can get quite large in size. There are a few useful pieces of “syntactic sugar” we use with structs and pointers.

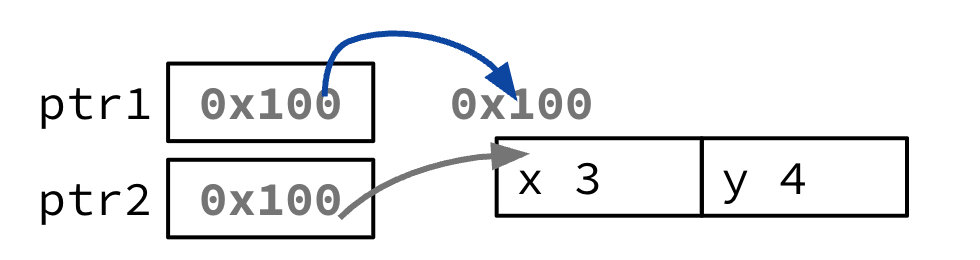

The code below declares two pointers[2] ptr1 and ptr2 to structs coord1 and coord2, respectively:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19typedef struct { int x; int y; } coord_t; /* declarations */ coord_t coord1, coord2; coord_t *ptr1, *ptr2; ... /* instantiations go here... */ /* dot notation */ int h = coord1.x; coord2.y = coord1.y; /* arrow notation = deref + struct access*/ int k; k = (*ptr1).x; k = ptr1->x; // equivalent

The dot operator

.is used to access struct members.The arrow notation

->is “syntactic sugar” (i.e., shorthand) for a dereference (*) and access (.). Here, we get value of thexmember of the struct pointed to byptr1.

Show Answer

The state is updated to Figure 10. Colloquially, pointers ptr1 and ptr2 now point to the same struct in memory @ address 0x100.

Figure 10:Starting state before executing the line `ptr1 = ptr2;

Sometimes it is easier to return to our definition of pointers as variables that store addresses. In this case, we are reading the value at ptr2 (0x100) and storing it into ptr1.

Java is also pass-by-value, though we should note that in Java, variables holding objects are inherently object-handles, i.e., references. This distinction explains the behavior of primitive Java types vs. Java “objects” when passed in as arguments. See more on Stack Overflow.

You may notice that Line 8 declares two pointers by mashing the

*next toptr1andptr2, respectively. We didn’t discuss it, but a single-declarationcoord_t* ptr1;is also valid. Most modern C programmers try to avoid declaring multiple variables on a single line where possible. But you’ll see it often in legacy C applications. Read more on Reddit.